Germany's Dragon Riders of the Great War

Abstract. Before the late nineteenth century, dragons were considered unsuitable for use in warfare for a variety of (fairly obvious) reasons. However, during and after the wars of German unification in the 19th century, European militaries began to reconsider their utility. In Germany, a government breeding program led to the development of the Fliegerwurm. With a wingspan of 9 meters, the ability to spew flame, and high degree of intelligence and loyalty, the Fliegerwurm proved to be a formidable weapon during World War I.

Keywords. Dragons, army, military, Germany, Kaiserreich, World War I.

Introduction

Prior to the late nineteenth century, dragons had not formed a reliable component of any European military. Attempts to harness their power in the service of armies had led to spectacular failures, such as at Sauherad in 1321, Mouton-sur-Mer in 1545 and Schaapwijk in 1678 when whole battalions perished in “friendly fire.” Mishaps involving the loss of civilian life also contributed to the dragon falling out of favour. For example, at Fårösund in 1709, fire-breathing flogdrekar turned back and gorged themselves on sheep at local farms instead of attacking the enemy fleet. When farmers ran out to protect their livestock, they were incinerated. Increasingly, such incidents came to be seen as unacceptable, and by the mid-eighteenth century dragons were no longer considered viable military assets.

In the aftermath of the 1848 revolution, a sea change took place, particularly in Germany. While the reasons for this attitudinal shift are beyond the scope of this paper, it was at this time that dragon breeders in Germany began to experiment beyond their traditional purview of purebred bloodlines.1 In 1867, the Ministry of Agriculture was tasked by chancellor Otto von Bismarck with developing dragons to specifications provided by the War Ministry. Their work reached its pinnacle in the Silberdrache and especially the Fliegerwurm.

The Silberdrache was bred for the smoothness of its flight and lacked the agility and firepower of the Fliegerwurm. However, its greater size and strength allowed it to attain higher altitudes than the Fliegerwurm. Therefore the Silberdrache served mainly as an observer and bomber.

Early iterations of the Fliegerwurm, a cross between the Prussian Lindwurm and Nordic flogdreka, played a major role in the sack of Metz and capture of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. Although it provided an unmatched advantage, its unpredictable temperament presented major challenges. It was slow to trust strangers, and in practice a dragon rider had to have raised his mount from the moment it emerged from the egg. The addition of Württemberger Ungeheuer to the Fliegerwurm bloodline after 1901 resolved most of these issues in the breed.2

Care of Dragons at the WWI Front

The physical hardiness from the Lindwurm bloodline made the Fliegerwurm well-suited to the weather and terrain of Flanders as well as the Russian front. They were not, however, impervious to the cold. Although they remained energetic even in low temperatures, the dampness of Flanders in particular bothered them at night; dragon hangars were set up specifically to shelter them. When forced to sleep outdoors, they preferred to do so under a tree in the company of humans; the reasons for the latter are not well-understood, but few riders begrudged their mounts this companionship.

Feeding Fliegerwurm at the front was not difficult. From the flogdreka bloodline came the ability to digest putrid meat, and the number of dead horses, donkeys, and mules was more than satisfactory. However, consuming too much meat that was too far gone resulted in scale rot and indigestion. The latter constituted a very real danger; in 1915, a groom lit a cigarette in the vicinity of a belching dragon and ignited a methane cloud that destroyed a nearby copse. Luckily, no lives were lost. The War Ministry introduced strict feeding and flame protocols in the aftermath of that incident.

Accounts of Fliegerwurm consuming human corpses are generally considered to be Allied propaganda.3 Official German sources emphasise that the safety of riders, grooms, veterinarians and other humans depended on not creating a connection between a human-shaped form and food.

Weaponry and Battle Tactics

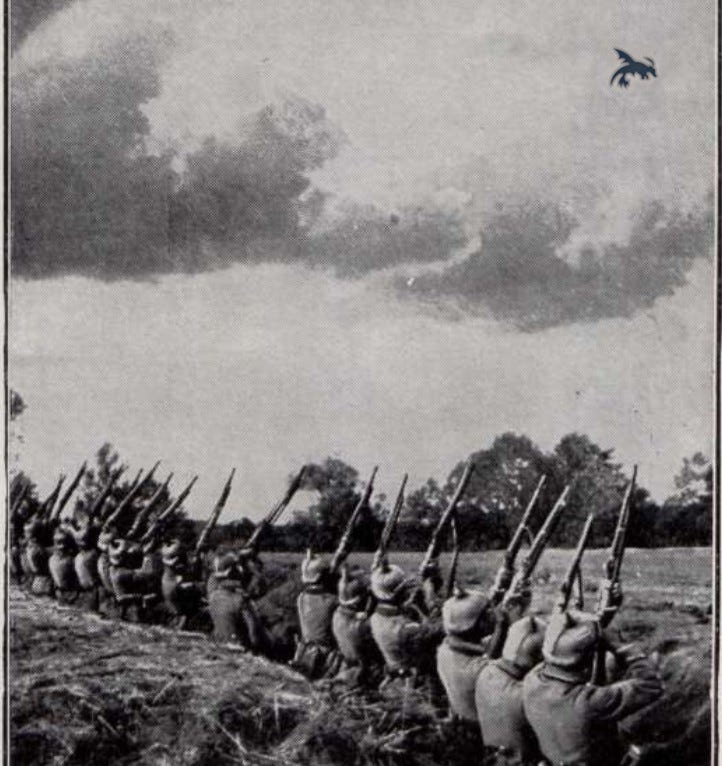

Fliegerwurm were, for the most part, impervious to ordinary machine-gun fire and flew too high for early artillery. As the war progressed, the power and range of anti-dragon weaponry increased to the point that only the Silberdrache could reliably fly out of range. Fliegerwurm riders began to emphasise 90-degree dives, hairpin turns, and zig-zag flight patterns, with generally successful results.

Obviously, fire played a major role in close combat and breeders therefore paid special attention to the quality and quantity of flame. The initial barrage of fire could determine the eventual victor; a dragon thus weakened would subsequently find itself more susceptible in close combat, when talons and spiked tails took over.

Attempts were also made to arm the dragon with mechanical means. One such experiment involved affixing a machine gun to the dragon’s hindquarters. A second rider sat facing the tail to operate the gun. This setup did not prove successful, primarily because their tails impeded effective use of the gun. The opposite was also true: Fliegerwurm were supremely conscious of any harm that their tails might do to the gunner. Hence they used their tails much more sparingly, in effect handicapping themselves in close combat.

Some early Canadian riders carried privately purchased harpoons into battle. At least three Silberdrache were killed by harpoon, but its use required a degree of expertise that made it impractical for most riders; most recruits to the dragon corps did not have the time to learn to wield a harpoon while at the same time commanding a dragon. The Canadians who claimed those kills had all served on whaling ships before the war; by the summer of 1916, they were all dead too and that was the end of the harpoon in the high skies.4

Dragon Riders

Despite their disparate geographic, economic, and social backgrounds, Germany’s dragon riders formed a tightly-knit corps. They were noted for their skill, fearlessness, and loyalty towards both each other and their mounts.

Riders experienced the Fliegerwurm’s intelligence as both bane and a blessing. The breed was easy to train, did not spook easily, and did not shy away from airborne battle, but also had a mind of its own and would sometimes act out of congruence with its human handler. In his memoirs, Karl Völker recalled that Erbemar once ascended 200 meters into a cloud bank, against repeated orders to hold his course:

Chilled to the bone and flying blind, I had to place all my trust in Erbemar. My lips were now too cold to utter a single word; and had I still been able to speak, a curse rather than a command would have rent the fog.

At that moment, a shadow appeared below us—an observer, by its wingspan probably a French Graoully. Were we not at war, I would have watched the sinuous grace of its flight with no little awe.

It seemed entirely unaware of us. Erbemar tugged the reins, I replied in the affirmative, and he dove towards the other dragon and its rider. They had no chance; I watched as Erbemar’s flame engulfed them and they plummeted blazing towards the earth.5

Winning a pitched battle depended as much on the relationship between rider and dragon as their prowess as individuals. Franz Ritter von Bergstutzen, for example, proved a competent rider when paired with Orendil, with whom he achieved the status of dragon ace with five confirmed kills. However, it was with Brandulf that he became legend. “They moved, acted, and even seemed to think as one,” wrote Völker.

On 24 July 1918, Bergstutzen was struck by anti-dragon artillery fire from the ground and died instantaneously. Brandulf bore his body back behind German lines; he is buried today at Neuville-St Vlaast in France. Brandulf returned to service with Kurt Tatzel. They were brought down by Wardrop Roxburgh and Cadfael, and died in October 1918.

Germany’s most famous dragon ace was Max von Liliengreif. The youngest of seven children from a Junker family, he was already an officer in the dragon corps when the war began. Liliengreif flew the Silberdrache Alager as an observation rider on the eastern front during the first year of the war. He then flew Sigelach, a Fliegerwurm, from the summer 1915; they achieved 80 confirmed kills together.

In May 1917, Sigelach was mortally wounded over Flanders by Sheridan Cockerill and Ianto. Liliengreif himself was only superficially injured but refused to abandon his dying dragon and died himself on impact when they crashed into a field. Cockerill later wrote:

It was a terrible sight. Those ragged wings, trailing dark blood through the sky; the dragon’s screams of pain as it tried to stay aloft, flames spurting from its nostrils; and Liliengreif holding on for dear life.

The dragon rolled its great shoulders as if trying to dislodge him, but he clung to the reins and, bracing himself, leaned forward. I used to do the same to reassure Ianto; I’d press myself along his neck and speak quietly to him, and by and by he would settle down. Of course, I was too far to hear Liliengreif’s words—but the dragon stopped flailing and its screams lost their edge. Ianto, sensing that the danger had passed, descended again and we watched as they tumbled to the ground in a mess of entrails and smoke.6

British soldiers gave Liliengreif a hero’s funeral. They also buried Sigelach, whose grave created a large mound in the landscape. It is now known as Zegeheuvel, or Victory Hill—a corruption of ‘Sige’ and the Dutch word for ‘hill.’

Conclusion

Dragons played a crucial role in the German war effort. According to Karl Völker, the psychological edge provided by the Fliegerwurm was unmatched. Not only did dragons strike fear and awe in the hearts of enemy soldiers at the front, the exploits of riders like Max von Liliengreif and Franz Ritter von Bergstutzen galvanised the public at home.

After the war, the Treaty of Versailles put severe limitations on the German military and, crucially, forbade the German government from maintaining a dragon corps. Perhaps for this reason, the dragons and dragon riders of the Great War have been almost totally forgotten. More research is certainly needed on this topic.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also like What Happened to the War Dead of Middle Earth? and The Adventure of the German Prisoner.

The Bavarian Wolperwurm, famous for its fearlessness despite its small size, was developed during this time. It became instantly popular, especially among the mountain-dwelling families of its native region, who prized its ferocity in the face of predators as well as its gentleness towards children.

Granheim, Sigmund. Drachenkunde. Hagen Vorlag, 1912.

See, for example, The Times of London, 10 May 1915, which quotes a “lieutenant-colonel serving with the Expeditionary Force in France.” According to this unnamed source, “The Canadians have done splendidly [at the Second Battle of Ypres]. But they are mad with rage because they say they have seen one of their men eaten alive by a dragon. This is not mere camp gossip. A general vouches for the fact.”

Later accounts, all anonymous, do not agree on the details. Various eyewitnesses claimed to have seen one, two, three, and even six men; in some accounts, they were already dead, in others their shrieks rang out as the dragon consumed them feet-first. Others claimed the dead man was a Scot, as evidenced by his legs, still kicking in their kilt hose, protruding from the dragon’s maw. A joint investigation by the UK, Canada, and Belgium in 1921 found no evidence of Fliegerwurm ever eating humans.

Tallis, Jane. “Whalers on the Western Front.” Journal of Canadian War History, Vol. 6, No. 6, June 2006.

Völker, Karl. Zwischen Himmel und Erde. Poppelmann Verlag, 1925. Völker was one of the few dragon riders to survive the war, but died in 1938 after being bitten by a rabid Wolperwurm.

Cockerill, Sheridan. Into the Sunset: A Dragon Rider of the Great War. Landon & Drake, 1934.