What did World War I sound like?

Given the lack of audio recordings from the battlefield, we can’t really know. But in correspondence from the front, German soldiers did their best to transcribe the “hellish music” of war for their families at home.

When the Great War began in 1914, radio was not used for civilian broadcasts, film reels were silent, and sound recording technology (of the kind that produced phonograph records) was too cumbersome to take into the field. The situation had hardly changed by the end of the war. Perhaps for this reason, only one audio recording from the battlefield was ever made: “Gas Shell Bombardment,” by William Gaisberg in 1918.

However, the authenticity of the Gaisberg recording has been debated for decades. It is now thought to be a “double- or triple-layered sonic artifact” — the result of careful engineering rather than a spontaneous moment of action in the trenches. (Nevertheless, at least one veteran of the war found it highly convincing.)

Print media also attempted to capture the atmosphere of the battlefield. In Germany, one such genre was the “Feldpostbrief” or “letter from the field.” Soldiers either wrote directly to the newspapers or to their families and friends, who then offered the letters to the papers for publication. For the most part, these men were not professional journalists or writers. Some of them veered into purple prose; others had a lighter touch. Upon publication, their contributions were almost always anonymized. Yet no matter their authorial prowess or their names, they all shared a common goal: to render life at the front with as much detail and realism as possible, including the noise of battle. They did their best to recreate the sounds of machine guns, rifle shots, artillery shells, explosions, and sea battles. Their letters, drawn from German newspapers as well as the 1937 book Der Deutsche Soldat: Briefe aus dem Weltkrieg, provide a unique glimpse into the soundscape of the war.

While soldiers frequently mentioned the chaos of battle, this disarray and disorientation did not necessarily result in cacophony. In fact, they often compared the sounds of battle to music. “A hellish concert of artillery began. It was a crackling, howling, and roaring whose equal I have never heard in larger skirmishes and battles,” wrote one soldier. According to Paul Oskar Höcker, who later published a book about his wartime experiences, “It is an evil music…We hear it whistling close to our ears, banging on our helmets.” At the same time, however, it lacked the coordination of real music. “The concert sounds like war drums and kettle drums without rhythm or beat,” wrote Albert Sagewitz.

A soldier at Ypres in 1915 made war sound like a symphony. “Then another shot is fired, as if hesitating, and then a rattle breaks out, a gruesome drumming, and singing and rustling fill the air. … There, a new beat in the music of death: the cold, brutal tack-tack-tack of the machine gun.” It was “a hellish music,” agreed another. “One’s nerves begin to rebel…” A soldier at Dixmuiden described walking over corpses and wounded— “and among all this misery, the sharp, whip-like cracking of the guns, the singing and whistling of the bullets.”

“The bullets sang eerily in the night,” he continued. The precise melody of that song, as it were, depended on who transcribed it. To that soldier at Dixmuiden, it sounded like “Päng — päng — päng!” To a one-year army volunteer at Fromelles, it was more of a “Pjjt, pjjt” but he was so tired that “exhaustion allowed us no fear. We only wanted to sleep, sleep; nothing else mattered.” Others thought that gunfire sounded like “pitsch — pitsch — pitsch!” A soldier from Görlitz described it as “simm-simm” and added that the sound “no longer excites us; it only gets dangerous when the shrapnel and shells are howling.”

These simulacra of gunfire can sound almost like child’s play. “All of a sudden: paff, paff — piu, piu — rurr — piuuuh! These were the first greetings of the French infantry,” wrote a soldier from the trenches. In the late 1920s, Bernhard von Fumetti used much of the same aural vocabulary in his wartime history of the Fusilier Regiment №80. In the regiment’s first battle of the war, they were surrounded by “whistles and hisses, bangs and cracks, piu-piu — clack-clack, in front of us, from all sides, and from the trees.”

French machine guns, according to one soldier, went “bätsch — bätsch — bätsch. Those broken things fire quite slowly; when ours started up batsch-batsch-batsch without stopping, we heard not a peep from the other side.” More commonly, however, machine guns made a tack-tack-tack sound. A soldier at Hartmannweilerkopf in the Vosges wrote, “Our machine guns began firing at once, their frantic tack-tack mingling with the crack of our mines and mortars.” Sometimes the sharpness of the tack was softened to dack: “Even when our shells exploded directly in front of and in the enemy trenches, the dack, dack, dack of the French machine guns could be heard like a mockery.”

The firing of heavy shots made a deeper, more sustained sound than a machine gun. “It’s like a factory here,” wrote a soldier, “in which the Kaiserglocken (cannon) rings constantly late into the night: ‘wumm, wumm, wumm!’” (The parenthetical reference appears in the original text. The Kaiserglocken was at that time the largest bell of Cologne cathedral.) At least one sailor heard the same sound at sea. “Now we see the bright gray wall of the ship’s side there — schsch — wumps; the shot has been fired.”

Once launched on their trajectory, artillery shells whined or wailed before they fell. “Sssss,” “sssssst” and “piiih” all resulted in a “bumm.” As one letter-writer put it: “Piiih — bumm — krach — the shells! …It’s a wonder that one doesn’t go crazy. …Don’t laugh; you have no idea what we endure here!” Other letters seem more blasé. “We let the shells rush over our heads. Hey, what ‘lovely’ music it is. Blummsss — si — su — — krach. A huge cloud of dust in the distance.”

Besides “bumm” and “krach,” things also exploded with a “bautz” or “bauz.” A particularly violent or unexpected explosion might occasion extra descriptive terms. A Pomeranian medic and his team had driven “about 7 kilometers in a rain of bullets and upon entering a ravine in the woods, bautz, bums, a shell hits the car, the driver is dead.” A German submarine captain reported similar sounds at sea. First came the rumble of the Russian guns: “Rum. Rums, one heard from shore…I gave the command to dive, schschschscht…bautz, there it was, two 40-meter-high columns of water, 50 meters next to the submarine.”

Heavy artillery drew comparisons to thunder both on land and at sea. “At 3.58 in the morning, two ‘packages’…exploded 500 meters behind us, rolling like thunder— ‘ramm, ramm.’ We call the large projectiles of heavy artillery ‘packages,’” explained the same soldier who had compared cannon fire to the Kaiserglocken. A sailor heading homewards after a night battle “stood on deck for a long time, staring into the spray from the propeller, dreaming of the stars. When I went on watch after a few hours, the sky was cloudy again, the night sultry — cannon shots thundered in the distance.” A soldier fighting in the Forest of Argonne also drew comparisons to a storm. “The muffled thunder of heavy artillery rolls in the distance. An eerily beautiful picture, but one that requires a great deal of self-control, courage and energy from those involved.” A teacher from Nassau in central Germany seemed to find it less taxing: “The hissing, whistling, crashing and thundering of the artillery…no longer bother us.” And watching recruits shoot captured Russian artillery and machine guns on the Eastern Front, another soldier observed that “one is already accustomed…to the constant Bum-viu-u-u-u-krach rrrrr, as well as the zooming of airplanes, both friend and foe, overhead.”

When those planes opened fire, their guns exploded with noise. “Bub, bub, bub; what’s that?” wrote Albert Sagewitz. “Then it’s next to us: rat, rat, rat. An enemy plane. The fog is thick; it’s hardly visible. Yet its machine gun with its bub, bub, bub still sounds above us.” The German machine guns answered soon enough: “tak, tak, tak.”

Sometimes these renderings of different sounds were not associated with any particular weapon. Instead soldiers combined all of them to create a general impression of the war. Paul Oskar Höcker depicted a battle near Lille thusly: “Sst — sst — — tuhiet — — — bumm, bauz, tscha . . . tacktacktacktack.” Others deployed these words in short bursts. “Hui! — Hui! — Hui!” wrote an officer about a forest battle in Belgium. “Branches crack…and between the trees, shrapnel sings its eerie song.” Later, as he and his men advanced further into the woods, “there is singing about our ears, first quiet, then ever louder — ssss — siih — — pitsch!”

Some writers used these onomatopoeias to break up the flow of their greater narrative, the staccato interpolations echoing the chaos on the battlefield. A soldier from the 81st Infantry Regiment gave this account of his very first battle, at Bertrix in 1914: “‘Onwards, hurrah!’ — Bumm…! The shock waves toss someone against a tree. I’m on the ground. ‘Hurrah! Get up, go on!’ — Bumm. This time I’m hit.” A few minutes later, “Bumm, bumm! Klaaatsch!…Shell after shell falls left and right, before and behind me…Ssssss — aha. Machine gun fire whizzes overhead.”

Battles were dominated by noise, so silence in this context took on a new significance. The lack of sound often contained an element of anticipation, as described by Fritz Frasch in a letter from the Eastern Front in 1916. “Grenades hiss over the dugout. A terrible crash. — The volley was too far…Quiet again! But it’s just the calm before the storm!”

Also on the Western Front, soldiers came to associate silence with an impending attack. “Now and then a stray bullet whistles over our heads, but otherwise there is silence, an almost eerie calm. In such dead silence, something is usually wrong over there with the enemy, and we are already prepared for unpleasant things.” Among those ‘unpleasant things’ were artillery shells. “You can hear them arriving from afar like an evil songbird, closer and closer,” recounted one soldier. They remained audible only until a certain point. “In the vicinity of the listener it goes quiet [and] everyone asks himself: where will it end up?” Earlier in the war, Paul Schwarzenberg drew an even more explicit connection between silence and death. After an artillery shell exploded in a forest clearing, he described the scene: “horribly mangled human bodies, illuminated by pale moonlight — and above all the uncanny calm, the rigidity of death.”

Music often accompanied soldiers into battle; fighting in silence could unnerve them. Without the accompaniment of drums, trumpets, and war cries, the battlefield became an uncanny and sinister place. “My hair still stands on end remembering the horrors of this night skirmish,” wrote a soldier on the Western Front. “No loud ‘Hurrah,’ no noisy drum rolls, no encouraging trumpet calls — we fought in silence everywhere. It was as if a ghostly battle had begun; men of flesh and blood do not fight like this.” His fear was not inexplicable or even irrational: to make no noise and to hear nothing were two hallmarks of the dead. Indeed, in German as in English, the link between silence and death manifests itself in the expressions “Todesstille” and “Grabesstille” — “deathly silence” and the “silence of the grave.”

A soldier’s family and friends came to fear a different kind of silence: the lack of correspondence, especially after a battle in which the soldier had been known to participate. August Kern’s family believed that he was dead after the Japanese defeated the Germans at Tsingtau. No letters arrived to suggest otherwise — until Christmas, when they suddenly received a postcard from their son, who was in good health at a POW camp in Japan. If such good news failed to materialise, families sometimes placed newspaper ads seeking information about a soldier’s fate. Emil Rennert was “wounded in Magneville Forest on 8 or 9 September, and since then nothing has been heard from him.” Rudolf Immel went missing a day later “on the Marne Canal, and since then no news is to be had.” As their families had likely suspected, this silence was indicative of their deaths.

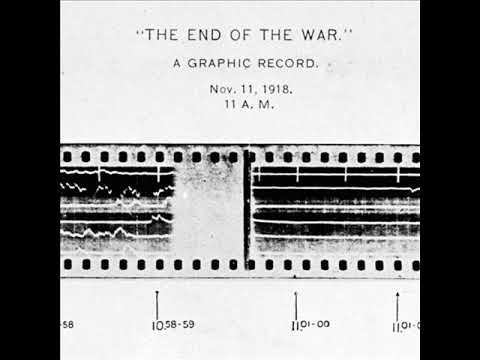

The noise of war finally ceased on 11 November 1918. Using seismic wave data from a “sound ranging” unit that was originally used to track the location of enemy artillery, the Imperial War Museum and sound production company Coda Coda reconstructed the moment that the armistice took effect. At last, “krach” and “bumm” and “piu” all came to an end, and the ensuing silence no longer meant death, but life.