The Rise and Fall of Zeppelin L20

How the fearsome "Raider of Loughborough" ended up in a Norwegian scrapyard during World War I

Throughout World War I, Germany sent out rigid dirigibles, also known as Zeppelins or airships, to terrorise their foes across the English Channel. The success of this campaign was questionable. Although German bombs set towns like London, Loughborough, and Great Yarmouth alight, they missed many crucial targets and Britons were not easily cowed. Nevertheless, the Germans never stopped trying. Thus it was that Zeppelin L20, in the company of six other airships, headed out on its latest mission on the night of 2 May 1916.

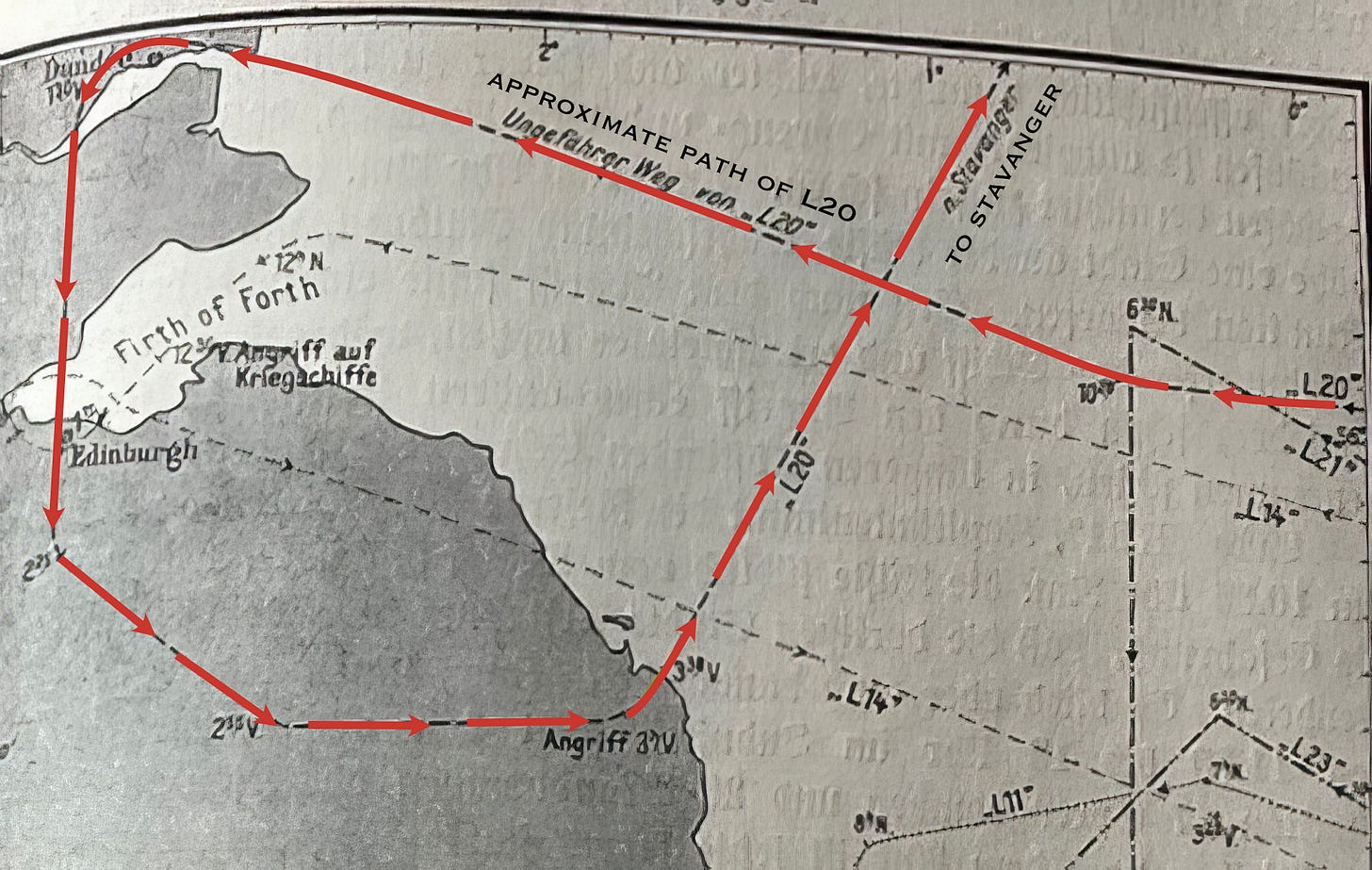

Their destination was Edinburgh, where the British naval fleet was anchored at the Firth of Forth. If the northwesterly winds held in accordance with the forecast, they would reach Scotland within a few hours. However, given the atmospheric instability that had lately tended towards thunderstorms, each airship commander had been instructed to change course and target central England if southerly winds prevailed.

“This is no May weather!” L20’s captain Franz Stabbert had told lieutenant Ernst Schirlitz that morning. Nevertheless, by 9.20 p.m., Edinburgh lay within sight. Then the weather turned against them. According to the official history, “At 11.20 p.m., L20—at 2100 m altitude—was caught in heavy rain and snow squalls, at 12 a.m. in dense fog.” One by one, all the other ships headed south; only L14 and L20 remained on course for Scotland.

The official history later described Stabbert’s refusal to turn back as being animated by “a lively spirit of attack.” However, this bellicosity, coupled with technical malfunctions, ultimately meant that L20 never returned to her home port at Tondern.

Twenty years later, Peter Vossen, who had been a machinist aboard L20 that fateful night, recalled:

A pitch black night enveloped land, sea, and airship…any attempt at orientation was impossible. …Where was sea and where was land? Below us we saw only the silent depths of darkness. …We cast out firebombs, which would disappear if they fell into the sea but which would light up and glow if they fell on land. Everything remained as black as before. Yet still the engine hammered on!

At 9 a.m. the following morning, the crew sighted the Norwegian coast. Only four hours of fuel remained; strong headwinds made progress difficult and rough seas precluded a water landing. Perhaps it was at this point that one of the men penned the message “We are in danger. Zep. L 20”, sealed it in a bottle, and threw it overboard. The bottle and its cry for help eventually washed up in Tungenes—about 15 km from Stavanger—in July. (The members of L19, which had gone down in the North Sea in February, also turned to messages in a bottle in their final moments. A British fishing vessel, fearing a hijacking, declined to pick up the German crew. Facing certain death, Captain Odo Loewe and his men wrote their last letters to their loved ones, packed the messages into a bottle, and sent it out to sea. It came ashore near Gothenburg, Sweden, in August of that year.)

Arrival in Norway

When viewed in the light of Zeppelin attacks on civilian targets in the UK, the excitement that greeted the first sightings of L20 in Norway may seem incongruous or even inappropriate. (Prior to the aborted Edinburgh attack, it had been nicknamed the “Raider of Loughborough” for its role in bombing that city.) However, Norwegians knew that Norway’s neutrality meant that they were not under siege; as Stavanger Aftenblad’s correspondent put it, the sight of “the great shining grey-gold bird, this masterpiece of human ingenuity, a cradle of death and destruction, a fearful symbol of the enemy” left witnesses on the ground “almost all speechless, not with fear but with wonder.”

Stavanger Aftenblad’s correspondent seemed to view the airship as a living creature, describing it by turns as “bird” and “beast” that “advanced calmly and majestically.” He imagined that L20 had survived cannonades on the Western Front only to be “mortally wounded” by the “Lilliputian mountaintop” with which it initially collided and which left the back of the ship, with its propellers and steering equipment, at a 45 degree angle to the ground.

“It’s not every day that something happens in Stavanger,” wrote “S.R.” for the women’s magazine Urd. As such, everyone came out to see it. “Bicycles, cars, carriages and cabs in pleasant confusion—ladies in office aprons and schoolgirls just let out of the classroom—inquisitive boys of all ages, besides a crowd of proper and ordinary people. Boats lined up across Hafrsfjord to see the wreck up close.”

The wreckage itself was a further source of amazement. Peder Krohn took a motorboat out to see this marvel of engineering and didn’t know whether he was more impressed by “the size, or the thoughtful and thorough craftsmanship beginning with the smallest things.”

Krohn described the wreck as if he were conducting an autopsy. “The foremost gondola was built to be quite open, with great celluloid windows; they were smashed. In the middle stood a great mitrailleuse. …The propeller had two wings and measured approximately 5-6 metres. …The inner skeleton was stiffened with a whole net of fine steel threads.” Meanwhile, S.R., writing for Urd, opted for a less technical turn of phrase: “It lay bobbing up and down like a huge broken eggshell.”

Krohn numbered among the souvenir hunters who got there early and hence got lucky. Bits of aluminium proved popular, as did the envelope; Krohn got a piece of the latter and sent it to the offices of Søndmørsposten “so that many more people can see it.”

The Crew

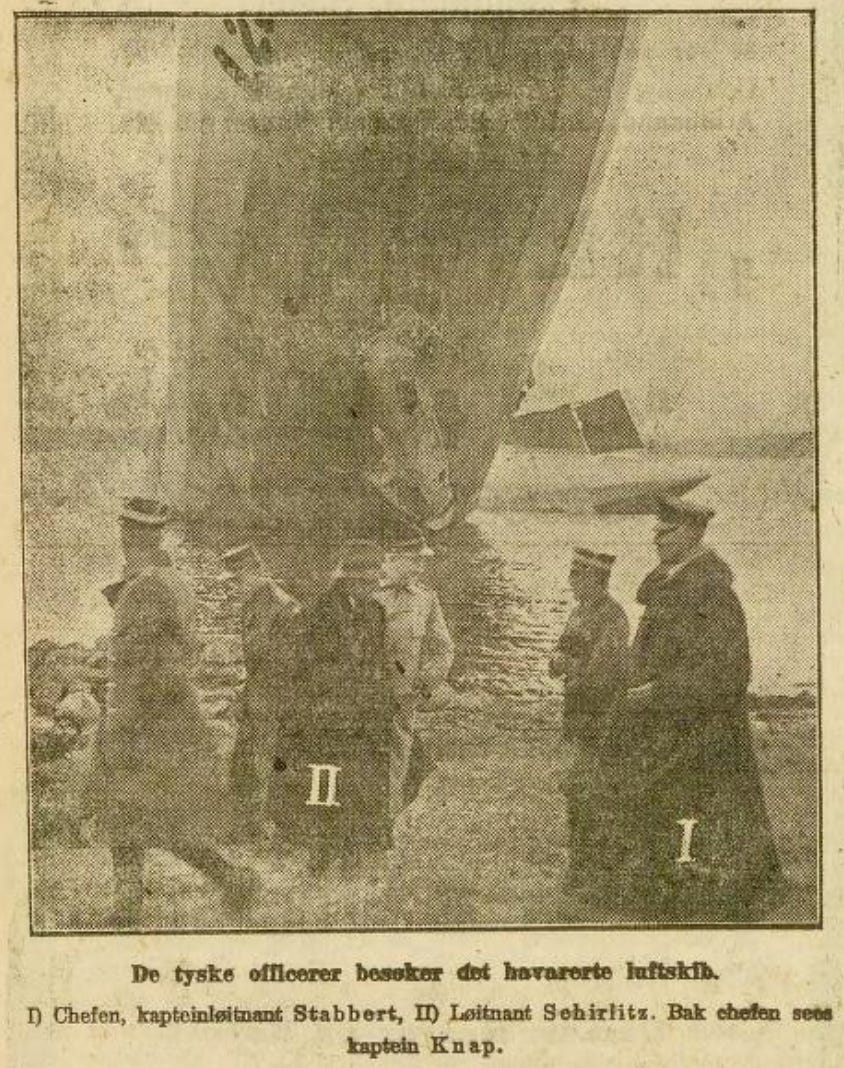

Newspapers at the time only named Captain Franz Stabbert and Lieutenant Ernst Schirlitz. The non-ranking crew remains less well-known even today. In 1936, survivor Peter Vossen said that they consisted of “Bavarians, Saxons, and the steward Hannemann, from Hamburg.” Vossen also specified Hans Peters as radio-telegraphist. Whatever their names and ranks, Norwegians in 1916 were still fascinated by them and their ordeal.

Thea Solheim found herself at the centre of the action after Stabbert and Schirlitz swam ashore and were taken to the nearby asylum at Dale where she worked. Stabbert, it was said ten years later, was still wearing his gloves when he emerged “in good condition” from the sea, while Schirlitz was in rather poorer form and was put to bed at once in the care of the asylum’s doctor.

Other civilians shared stories of their encounters. The trade functionary L.W. Hansen met four men who had been cast out of the gondola when L20 hit a cliff. One of them was badly wounded and “asked if he could return to Germany. He was amazed to hear that it was not possible. He seemed quite crushed and repeated many times: Ach, dieser Krieg, dieser Krieg!” The others, however, were in better spirits and “they had hardly gotten to their feet before they lit their cigarettes.” The injured man was taken by car to the military camp at Malde; the other three went by bicycle. For these men, wrote S.R., “there was nothing but a feeling of German-friendliness…people are people, or at least that’s how it ought to be.”

Although civilians may have evinced open-heartedness, the military did not. At Malde, the reception was rather less friendly. Strict security measures were put in place: soldiers patrolled “with bayonets on their weapons, and no one was allowed to speak to the Germans. Iron bars have been installed on the windows.” While these initiatives may sound over the top, the Norwegians had good reason to be wary: sailors of Berlin, interned at Hommelviken near Trondheim, had made regular attempts to escape since 1914 and in 1915 Berlin’s captain actually made it all the way back to Germany, after which a triumphant telegram was received aboard the ship.

Five of L20’s crew were later released from internment. They were the lucky ones who had been picked up outside Norwegian territorial waters. This was the wartime norm; the Norwegian government had adhered to the same principle in the cases of the British ships Weimar and HMS India in 1914 and 1915 respectively. The others were interned at Hommelviken with the sailors of Berlin.

That summer, internees at Hommelviken attempted to escape no less than six times. Although these escapes were all foiled, Captain Stabbert followed the example of Berlin’s Captain Pfundheller and eluded his captors in late November. Stabbert spent the day in town, as was his wont, then returned to the ship in the afternoon and ostensibly disappeared that night. No one was quite sure precisely when or how he managed to do so; it was claimed later that he had been assisted by the captain of the German steamer Ebersberg. Like all other officers, before his trip into town that day Stabbert had been required to give his word of honour that he would return, and it was noted with some irony that he had not actually broken his word since he had not absconded while on leave. He later commanded another airship and died in combat over France in 1917.

The Fate of L20

The remains of L20, especially its hydrogen-filled envelope, presented a problem in the days after the crash. It was, the Norwegians thought, only a matter of time before it tore loose from its moorings and began to sail willy nilly over the countryside leaving destruction in its wake. While the German official history states that L20 was destroyed by the crew, the Norwegian press tells a slightly different tale. On the orders of Captain Johannessen, Sergeant Aalgaard was dispatched with ten men to put the wounded ship out of its misery. At 3.05 pm, “from a distance of 120 meters…they fired salvos at different points on the airship. It exploded with a terrible bang…”

Aalgaard and his men were thrown back by the force; the explosion was felt as far away as Stavanger, eight kilometres away. The roofs of nearby boathouses were destroyed, their shingles broken and blown away (according to other reports, they also caught fire). Windows blew out of farmhouses, the glass shards injuring children. The airship itself was burnt to a crisp: “Only the aluminium skeleton remains, together with a spiderweb of shining metal threads.”

The Norwegian pilot Tryggve Gran, who had recently flown the first nonstop flight from England to Stavanger, was asked whether he thought the Germans were upset about the destruction of the zeppelin. He replied, “I don’t think so! The explosion certainly took place in accordance with their knowledge and wishes.” Indeed, the official history records the dumping overboard of “classified information, the rest of the explosives and firebombs, as well as the radio-telegraph equipment” and one of the crew, a corporal, confirmed that their priority had been to safeguard the ship’s technology: “We drifted with the wind until we reached the Norwegian coast. Even though it meant death, six men offered to stay on board and destroy the machinery so that no one could learn the secrets of the ship’s construction. The rest of us jumped.” (Bergens Aftenblad told a slightly different story: after the captain issued the order to abandon ship by jumping into the fjord, eight men, not six, remained on board because they were poor swimmers.)

In September 1916, the earthly remains of L20 were taken to Kristiania by the steamer Mira. Crowds gathered to welcome the ship, whose decks both fore and aft were “covered with scrap, which reached a great height.” Mira lay in at Revierbryggen, a pier close to where the opera house now stands, and L20 ended its days in a scrap depot at nearby Akershus fortress.

Conclusion

L20 may have met an anticlimactic end at Revierbryggen with its crew in captivity at Trondheim, but one can argue that this conclusion to its saga was better than that of many other airships. The British began using explosive bullets against Zeppelins, which ignited the hydrogen-filled envelope and turned the airships into fiery infernos of death. The crews of L21, L31, and L32 perished in this way in the autumn of 1916. By contrast, all but three members of L20’s crew survived. Moreover, because L20 came down in a neutral country, its technological secrets remained safe from the inquisitive eyes of the enemy. Such was not the case for L49 (captured nearly intact) and L33 (partially destroyed by its crew after an emergency landing in Britain), which inspired later Allied airship designs. In short, while a better fate for L20 may have been possible, a worse one was more likely.