Sütterlin, Soldiers’ Postcards, and Staying Connected in the Pandemic

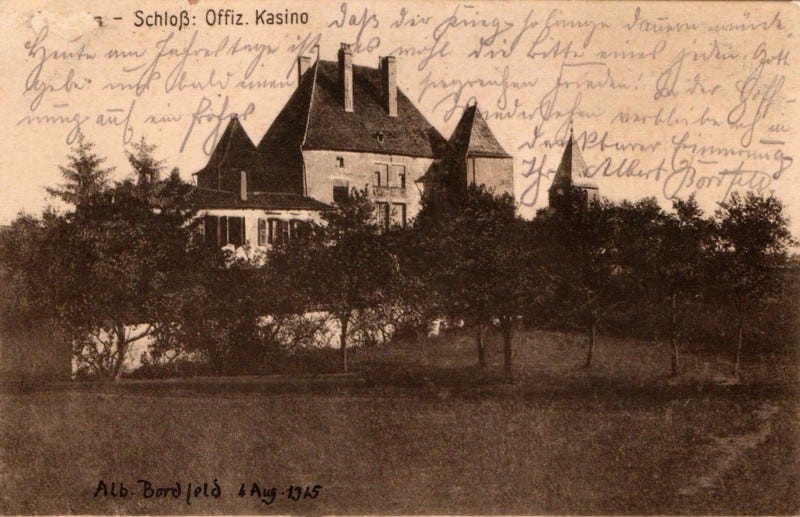

On 1 August 1915, German army reservist Albert Bordfeld sat down and wrote a postcard to the reverend pastor in his hometown of Ohrum in Saxony. “How are you all doing?” he asked. “Hopefully very well. Who would have thought that the war would last so long?”

One year prior, on 1 August 1914, the Great War — World War I — had begun. Few expected it to drag on for more than a few months. As Bordfeld put it, “Today, on the anniversary of the war’s beginning, it is likely the plea of one and all: God grant us a victorious peace!”

I first read these words almost precisely a year after the very first COVID-19 lockdown in Norway closed schools, shuttered shops, and emptied streets. At the time, the pandemic was estimated to last anywhere between a few months to a few years. Twelve months on, this soldier’s message struck a chord: we find ourselves again in lockdown and although vaccination is in full swing, “victorious peace,” as it were, still seems quite far off.

Transcribing and translating Albert Bordfeld’s words was part of one of my pandemic projects: to learn to read the archaic German script known as Kurrentschrift and its simplified form, Sütterlin. Kurrentschrift was used in German-speaking countries for approximately 500 years — from the 1500s to the twentieth century. For anyone with an interest in German history, the ability to read it is indispensable.

Having nearly failed paleography as a master’s student, I lacked both confidence and optimism that I would ever manage to unlock the secrets of Sütterlin. Multi-paged letters and journals overwhelmed me. For months I despaired, and decided to knit socks instead.

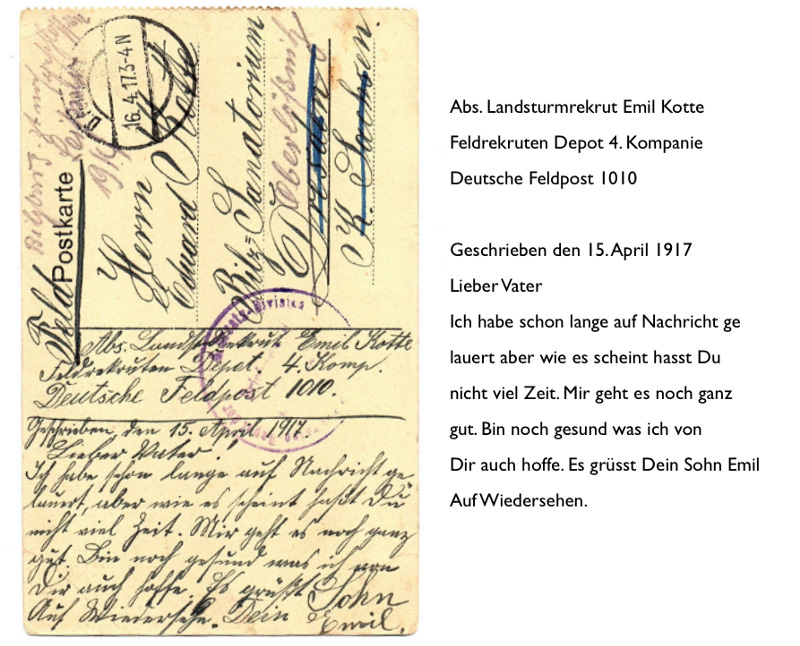

Then, entirely by chance, I came across a post on the Great War Forum. A Brit had asked for help deciphering a postcard written by a Saxon soldier in 1917. Emil Kotte wrote in a clear and elegant hand, and none of the forum regulars with expertise in Sütterlin had yet replied. I can do this, I thought.

So I did.

Mick, the Brit, was thrilled to be able to read the century-old message. For my part, I was ecstatic at the now very real possibility of success in Sütterlin. So, because Mick collects postcards written by German soldiers of the Great War and I need Sütterlin practice, we joined forces: every few days, he posts a picture of a new postcard in the forum thread, and I begin the task of rendering it into something legible.

Because I was educated as a medievalist and accustomed to dealing with the distant past and dead languages, World War I has always seemed to me to be incredibly close in time as well as academically accessible. Though I’m cognizant of the danger of believing people in the past to be just like us, I’m nevertheless always struck by our common humanity.

Health and well-being is a constant theme in these postcards. “I’m still healthy and cheerful, and hope you are too,” wrote Christian Ahrens in September 1915; “Tomorrow I’ll be at the Minenwerfer.” Emil Kotte’s message to his father was much the same: “I’m still doing pretty well. I’m healthy and hope the same of you.” The latter sentiment is particularly intriguing because the card is addressed to the Bilz-Sanatorium in Oberlössnitz, Saxony — a healing spa founded by Friedrich Bilz to treat all manner of disorders. Absent any other correspondence, though, we can’t know why Emil’s father was there or whether he ever recovered.

The same wishes for good health persist more than a century later. “I hope that smoke, floods, hail, & coronavirus are not wreaking too much havoc in your life, & that you are keeping calm & carrying on,” I wrote to a friend in Australia at the beginning of 2020, utterly oblivious to what the rest of the year would bring. “Hope everything is well with you and your family under this coronavirus outbreak,” my friend in Hong Kong wrote to me a few months later, where in addition to the pandemic they were also contending with the Chinese government’s attacks on freedom of speech and democracy. Yet her messages betrayed none of this political turmoil. “This is my first time using watercolours for painting,” she wrote on a hand-painted postcard. “It’s much harder than colour pencils!!! The water is just totally uncontrollable.”

Similarly, in the postcards that I’ve translated so far, soldiers rarely referenced the war directly. (Letters are another matter.) However, the scenes that they selected often tell another story. Oskar Johne chose a picture of smoke billowing from the town of Pagny sur Moselle after an attack in August 1915. Alfred Uhlig sent a homesick message to a friend on the back of a photograph of Malancourt. The town had been completely destroyed; only ruins remained and a dead horse lay in a pool in the foreground.

Of course, not all postcards showed such overt images of war. Less graphic selections were available for the more faint of heart. Richard Grundmann sent his sister a card depicting a motley crew of uniformed men: “my recruits — but it’s not a good picture.” Rudolf Wagner’s mother received a view of a field bakery, the bakers standing almost comically in line as they carry their wares on their shoulders.

Some soldiers pined for normalcy and a return to pre-war life. “Everything was nicer at home,” bemoaned Private Herrmann of Infanterie-Regiment 93 upon his return to the front lines. “Oh, if only this would come to an end!” Exactly 104 years to the day since he sent that postcard, I transcribed his words with a great swell of sympathy in the midst of yet another lockdown.

“I wish that I could go to the bar, but they’re all empty here,” Alfred Uhlig confided to a friend. “And there’s no beer in the trenches.” This lament retains its relevance today. Restaurants, bars, and cafés are all closed to sit-down customers. Recently, a friend sent me a postcard from a steakhouse in Milwaukee — the table laid for guests, deer antlers presiding over the scene. I wrote back to him to say that was the first time in over a year that I’d seen the inside of a restaurant.

The German Feldpost — military mail service set up to provide near-constant postal communication between soldiers and their families — also made it possible to receive food from home at the front. Christian Ahrens, writing from the trenches in the fall of 1915, asked his family to “please send eggs and butter.” Although we may assume that the eggs were boiled, one could in fact send fresh eggs in special boxes that supposedly guaranteed they would arrive whole and unbroken. Sweets, alcohol, and bread also passed through the Feldpost.

“I received your chocolate, for which I thank you very much, dear Milly,” wrote Oskar Johne to a female relative in an undated postcard. Likewise, as the COVID-19 pandemic entered its second year, a friend in Chicago wrote to me that my Christmas packaged had finally arrived: “The candy bar was delicious!” (As it should be; it was white chocolate with gingerbread pieces made by the Norwegian chocolatier Fjåk.)

In the same way that food from home supplemented soldiers’ rations, gifts of food have sustained us during the pandemic. They’ve served as a mechanism of care and affection in world where we’re always thinking of each other but unable to meet in person. We sent homemade Christmas cookies to my mother-in-law and Norwegian licorice to Dutch friends. My brother put together a package of American candy for my kids for “tasting purposes”; from a friend in Chicago we received banana Twinkies, maple cream oreos, and cinnamon-flavoured Red Hots. For the past year, we have sent and received the same sentiments (albeit with less formality) expressed by Johann Maier in his card from a POW camp in France : “Allow me to hereby send you my most sincere thanks for the parcel.”

I am an old millennial. I remember a time when letters across a continent were the only affordable way to keep in touch with my childhood friends, and I don’t think that I will ever come to love my Kindle in the same way that I love my dog-eared, ragged copy of Lord of the Rings. Yet I can’t help the fact that I live in a world of digital ephemera in which my words on the screen look the same as anyone else’s.

Perhaps that’s why these handwritten postcards appeal so much to me. Every card is a window that opens onto a specific time, place, and person, and each man tells his own story by his own hand. He might well self-censor, of course, but his words haven’t been tidied or edited or set in impassive and impersonal type to serve a greater historical narrative.

For a moment, we can sit beside Christian Ahrens in his trench as he scrawls a reply to his parents and grandfather; we shiver in the “terrible cold” along with Rudolf Wagner; like Emil Kotte, we long for news from faraway family and friends. We understand their discomfort, joy, and melancholy because it is our own. And just as the physicality of these postcards links us to the past, cards sent in these “corona times” also provide comfort in the present. We can’t touch each other, but we can trace the shapes of the letters formed by our friends and we can read words that they wrote just for us. We can imagine them at their desk or kitchen table, pondering their next sentence; we can see where they turned a period into a comma and a comma into a semi-colon. We know that they touched this paper; even if it was two weeks ago or two months ago, they held it in their hands, just as we are doing now.

“I always get a lot of attention in the apartment lifts when I get one of your cards from the mailroom,” a friend in Australia told me. “Handwritten messages are becoming very rare in today’s world! People are really fascinated to see how far they’ve come too.”

These postcards might have traveled 15 000 kilometers or 100 years. They might be addressed to us or not. Perhaps they were written by a friend in quarantine or a soldier at a recruitment depot. Whatever the case, we might never send a reply. But if we do — whether by post, e-mail, text message, or chat app — it will inevitably echo that of Alfred Uhlig, writing to his friend Franz Garscha during a wartime summer: “It was with great pleasure that I received your card.”