Not Your Great-Grandmother’s Knitting: Sock Production in World War I

During World War I (1914–18), knitters from around the world made millions of socks and other garments for soldiers serving at the front. Today, two assumptions about this work dominate the popular view: firstly, that knitting was the exclusive purview of women and girls; and secondly, that socks were knitted one at a time by hand.

However, the truth is more nuanced. The need for socks was so great that two-at-a-time sock techniques, crochet, knitting machines, and men were drafted into service to supply them.

“Siamese Socks”

Twenty-first century knitters talk about “second sock syndrome,” which refers to the lack of will to knit a second sock to complete the pair. While this particular terminology likely did not exist a century ago, wartime knitters were quite familiar with the problem. Back then, the solution came in the form of “Siamese socks”— the process of knitting two socks at once on the same set of needles.

This method, nowadays known as double-knitting, was said to come from Australia. Supposedly, Australian women finished 50 000 pairs of socks a month using this method. However, as the New York Sun conceded, “it is something to test the skill of the superknitters to narrow and knit two heels at the same time.”

The phenomenon traveled to the farthest corners of empire. The Matura Ensign of New Zealand reprinted the article verbatim from the American papers, even preserving the description of Australia as “the land of queer things.” The same article also appeared in the Australian press, though in a modified form: it made no mention of the technique’s so-called Australian origin and most certainly did not refer to the country as queer.

How does one go about knitting “Siamese socks”?

Two balls of yarn are used, one for each sock. The thread of one runs over the right forefinger. Cast on double the usual number of stitches, first of one thread and then the other. Then knit one and purl the other. That’s all there is to it. Easy enough!

…there’s fascination in working it out and great satisfaction to find one sock growing inside the other. The “right sides” will be together on the inside. The outside will show the “wrong side.” Get it?

In case those instructions weren’t “easy enough” and you didn’t “get it,” this video may help:

My conversations with Australian knitters suggest that women there did not historically knit their stockings two at a time. In fact, the origins of the technique are certainly older than the Great War and likely not of Australian origin; for example, Anna Makarovna in Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace knits socks in this way.

Crocheted Socks

Crochet uses a single needle with a hook at the end to manipulate stitches. It produces a fabric that is denser than knitting and also much less flexible. These days, crochet has a bad reputation and inevitably brings to mind doilies and old-fashioned grandmothers. However, when it was first documented in the nineteenth century, it was often used to mimic both bobbin and needle lace. Of course, it could also be put to far more utilitarian uses, and while knitted socks from the Great War are more well-known than their crocheted counterparts, patterns for crocheted socks and other soldiers’ accessories appeared throughout the war.

In France, crochet was particularly popular at the beginning of the war. Among the instructions for gloves, mittens, and balaclavas, the newspaper Le Temps printed a pattern for a crochet sock in November 1914. Later, another pattern appeared in the booklet La Femme et la Guerre (Woman and War). In September 1915, Les Annales politiques et littéraires published a pattern for “crocheted trench socks.” Mrs Brémont, who sent the pattern, was kind enough to enclose a sample sock as well; it was, the editor wrote, “very practical and soldiers have already benefited from them” despite the fact that, “at first sight, the general aspect [of the sock] is unconvincing.”

Crocheted socks also experienced a measure of popularity in other countries. According to the Leader of Melbourne, Australia, “Crocheted socks for our soldiers at the front are much quicker and easier to make than knitted ones; they are also more durable.” Not to mention that if they were washed “in tepid (soapy) water, dried, and pressed before wearing,” they became “soft and extremely comfortable.”

While women may have eagerly cast themselves into the crochet fray, the garments that they produced were less than ideal for military use. Regarding the desirability of “crochetted articles” for the war effort, a branch of the American Red Cross informed volunteers that “The war authorities in France prefer not to have them. They are bulky, and seldom warm enough.” Other aid organisations similarly preferred knitting because it produced items that were “light and elastic.”

Perhaps for this reason, crocheters began to focus on the production of hospital socks, also called bed socks, for convalescent soldiers. Bulkiness, inelasticity, and lack of warmth presented less of a problem for relatively immobile men housed in a clean indoor environment. As one newspaper assured crafters, in such a setting a crocheted sock “would be found very comfortable in wear, as it keeps the bandages in place without any pressure.”

The use of crocheted socks in hospitals is perhaps not surprising; medical facilities accepted a variety of socks, including tube socks and spiral socks in both crochet and knitting. Yet whenever crochet attempted to claim a place alongside knitting as an equal, rather than inferior, craft it met firm resistance. As M.H. Mackay wrote in a letter to the Bendigo Advertiser, even hospital socks ought to be knitted because they “take less wool than crocheted ones, and wash better.” The former is certainly true; given the density of crochet stitches and the ways in which the yarn must be twisted to form them, the latter claim is also plausible.

Few crochet patterns for any soldiers’ comforts appeared in German-language media during the war. Donation lists from the early months of the war contain few crocheted items in general, none of them socks. Germany’s acute wartime wool shortage may explain the preference for knitting. The hospital slippers pictured below are an exception; it may be relevant that the pattern was published in 1914, when wool was still relatively readily available.

Generally speaking, the exacting standards for combat socks meant that knitting predominated in all combatant countries. As a French newspaper eventually admitted, “We can’t crochet everything; socks in particular are deplorable.”

Machine-Knitted Socks

Although sock production for soldiers during World War I is usually associated with handknitting, machines were in fact used as well. Some countries seem to have had only basic knitting machines. In Germany, for example, newspapers describe machines as capable only of knitting sock cuffs. Heels and toes, it seems, were beyond them. Similar limits occurred in New Zealand as well: “It saves time to get the tops of the socks done on a knitting machine, but, as of course everybody knows by this time, the feet must be hand-knitted.” However, as Shelly Hatton demonstrates in the video below, it is entirely possible to turn heels and knit toes by machine.

In Canada, the Red Cross furnished families with Gearhart sock knitting machines and 10 pounds of wool. If they delivered 30 pairs of socks, they could keep the machine. Each sock took approximately 40 minutes to make; Red Cross offices in the United States recorded similar times. Even the fastest handknitters could not compete with these speeds.

Besides vastly improving efficiency, sock-knitting machines also allowed non-knitters to feel that they were contributing to the war effort. For example, every evening Mr. de Lacey Evans, “one of Baltimore’s best-known financiers…sits down at a knitting machine and turns out a pair of socks before he retires for the night. Mr. Evans has adopted this unique method of showing his patriotism because he has passed the age of military service.”

Mr. Evans’ motives might have been honourable, but his efforts smack slightly of a vanity project. As we shall see, being past the age of military service and being a man have never precluded learning to knit by hand. Moreover, the machine would have been more productive at a Red Cross office where it could have churned out socks all day long rather than a single pair in the evening.

Men Who Knit

As the case of Mr. Evans illustrates, men and boys who were too old or too young to join the military sought other ways to contribute to the war effort. In the United States in particular, many of these eager male volunteers turned to knitting — and even if they weren’t eager, they were encouraged all the same. The following song, for example, seems intent on making its young singers in the Minneapolis public schools believe its words. It was sung to the tune of George M. Cohan’s popular march “Over There,” with the determined cheerfulness in both lyrics and tempo that is so characteristic of American knitting songs of the time:

Johnnie, get your yarn, get your yarn, get your yarn;

Knitting has a charm, has a charm, has a charm.

See us knitting, two by two.

Boys in Whittier like it too.

Hurry every day, don’t delay, make it pay.

The final verse of the song strongly suggests that the boys are knitting patchwork squares for blankets. Squares required less skill to make than socks and were thus a good project for beginners. Because they were used in hospitals rather than in combat, they could also feature stripes and bright colours, both of which made the work more interesting.

Men were not limited to blankets and scarves, however. In Australia, E.W. Underwood acquired the nickname of “Crochet King” for his expertise in the craft. He had learned to crochet while recovering from a broken leg in childhood. During the war he sold and raffled his filet crochet and Irish crochet creations to raise money for the war effort; newspapers described him as “the only man known to be selling fine lace of his own making for the funds.” He also made at least 150 pairs of socks, though their use may have been limited to hospitals.

Soldiers themselves also knitted. According to an article in the Casseler Neueste Nachrichten in 1915, “Our renowned German troops can not only dig trenches and defend them; they can also cook and even knit.” A soldier known only as Friedrich was described by one of his fellow soldiers as “a comrade here who knits. He has already knitted himself one pair of stockings and has started a second.”

While Friedrich’s skill set may have given rise to surprise among his trenchmates, knitting and other needlework was not uncommon among their British counterparts. As early as the Crimean War in the 1850s, convalescent British soldiers had been encouraged to learn to knit and embroider. During the Great War, wounded British and Empire soldiers turned again to knitting and especially to embroidery to pass the time; “the attraction is thought to exist in the novelty, the bright colours, and the slight exertion necessary,” wrote The Sun of Christchurch, New Zealand. “The sick men can lie back in bed and ply the needle at their ease.” Exhibitions of soldiers’ handiwork were mounted in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, with their work described as “striking,” “excellent,” and “a marvel of needlecraft.”

Wounded German soldiers also learned fiber arts. The German Red Cross published an instructional booklet in loom knitting and macrame for use by convalescent soldiers in military hospitals. Loom knitting seems to have been chosen for its simplicity. According to the author of the booklet, “it is surely a relief for unpracticed hands — i.e. those of boys and men — to hold a solid board rather than thin, pointy needles.” The first pattern in the book consisted of a narrow scarf about 10 cm wide with a knotted fringe. It was accompanied by the suggestion that soldiers make it “in white with pink or blue stripes” for their young daughters or “entirely in white or dark blue” for their wives. Should they want to outfit themselves or their comrades, however, a wider, unfringed version was preferred; “fringes use a lot of yarn and are totally useless.”

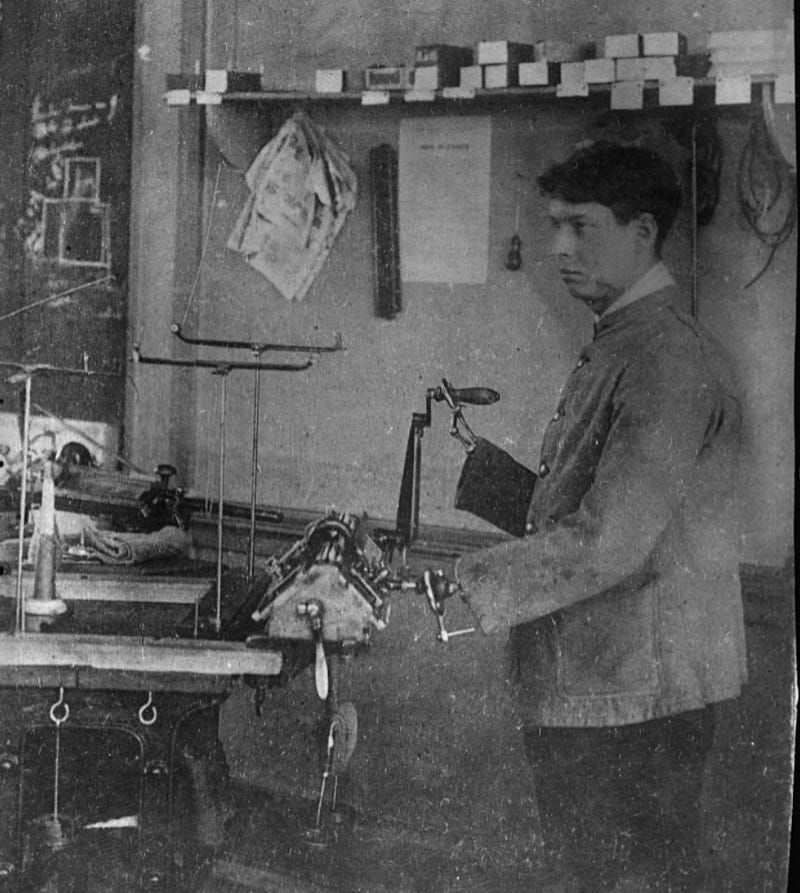

During and after the war, attempts to provide gravely wounded veterans with marketable skills led to the establishment of various trade schools. At one such school in Neuilly, outside Paris, blind amputees were taught to use knitting machines. They produced goods such as sweaters and jackets for commercial sale.

Conclusion

During the war, knitting was an inclusive activity. It was not limited to little old ladies of European heritage; men and women of all ages, people with disabilities, and people of colour all sat down to make socks and other garments for soldiers. Rich people, middle class people, and working class people knitted— at home, in parks, at Red Cross offices, even at school. They used different handknitting techniques; sometimes they used machines. Whoever they were and however they did it, everything that they produced was gratefully received by soldiers at the front.