Who Were the Hun?

Who were the Germans of the Great War? “Hard people to beat,” observed the American surgeon Harvey Cushing in his journal from the Western Front; “big, strong, cheerful, and well-fed” too. Though he noted the names of seemingly all the Allied soldiers with whom he crossed paths, he never mentions the name of a single German, instead referring to them with all manner of pejoratives. One can hardly fault him; to Cushing they were the enemy who caused the carnage that he witnessed in Belgium and France, including the aftermath of one of the first gas attacks in 1915. To their families, friends, and colleagues, however, these men were more than their actions on the battlefield. Their relationships with the soldiers derogatorily nicknamed “Fritz,” “the Hun,” and “the Boche” can be glimpsed in death notices published in Hessian newspapers between 1914–1918.

On 18 November 1914, the families of Heinrich Diemer, Johannes Sauer, and Lorenz Oesterling — respectively “our dear son, brother, brother-in-law, and uncle,” “our dear son and brother,” and “my beloved husband and my children’s faithful father” — announced their deaths in the Casseler neueste Nachrichten. Such examples were repeated, almost unchanged, hundreds if not thousands of times over the course of the war. Towards the end of the conflict, in October 1918, the Darmstädter Tagblatt published the death notices of Peter Stromberger, Philipp Laub, and Martin Sames: “my beloved husband, loyal father to his children, our dear son, son-in-law, brother, brother-in-law, and uncle,” “my good and loyal spouse” and “our dear colleague.”

As the war continued, second and even third sons died in battle. Wilhelm Jahn’s parents memorialised him saying that he “followed his dear brother Gustav (who died on 14 April) into eternity.” A week before the armistice, Johann Bernhardt’s family announced that “now our second kind, brave, dear son…followed his brother Heinrich Bernhardt, who fell on 13 October 1916, into death.” In 1917, the Gunkel family announced the death of “our oldest, beloved, unforgettable son and brother Karl… He followed his two dear brothers Willy and Heinrich, who died in 1914 and 1915 respectively.”

Those dear sons and faithful fathers, recipients of the Hessian Medal of Bravery, the Order of Albrecht, and the Iron Cross, served in a range of capacities in the army. A parade of fusiliers, musketeers, infantrymen, lieutenants, and lance corporals marches through the death notices. Notably, men who had careers before the war might be described as such, their professions defining them more than their military roles. Otto Falke was a factory owner; in the 33 months that he served before his death, he won the Iron Cross. Karl Müller was a teacher. Hyacinth Lieber was a lawyer. Before the war, Karl Steinacker was a streetcar conductor; Eduard Grosskurth was a locksmith; Hermann Hatzmann was a blacksmith. Carl Weissensee was a pharmacist. Kurt Blass, decorated multiple times for bravery, had been a student of theology before enlisting; 18-year-old Karl Theodor Köppler was an “Abiturient,” a high school graduate. Isidor Menges, Ildephons Müller and Daniel Rosenbach, who all died within a week of each other in 1915, were Franciscan monks from the Frauenberg monastery at Fulda.

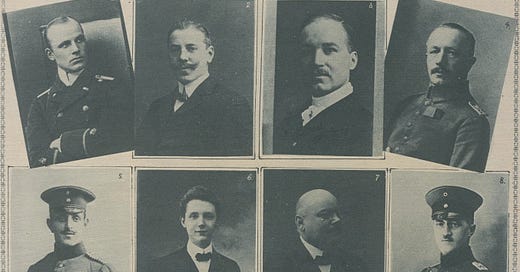

Princes died alongside these tradesmen, students, and professionals. At the end of October 1914, the Casseler neueste Nachrichten printed an article that listed members of German princely houses who were serving in the military — including seven already killed in action. One of them was Prince Maximilian of Hesse, who had died a week earlier in Belgium; his brother Prince Friedrich Wilhelm died two years later at Cara Omer in Romania. Their deaths were of sufficient importance to be reported on the front page of newspapers at the time. Lesser nobility was relegated to the personal advertisements page with everyone else. Their death notices do not differ noticeably from those of non-nobles. Thus the count Theobald Graf von Geldern-Egmond appeared in a modestly sized notice next to the teacher Heinrich Schmidt while Baron Hugo Freiherr von Nordeck zur Rabenau shared a page with the cigar manufacturer Julius Menges.

Employers as well as family often placed announcements (“Nachruf”) to acknowledge their employee’s death as well as the deceased’s personal qualities. After Georg Hormel died at Ypres in November 1914, the owner of Cafe Markees in Marburg memorialised him as “my dear long-serving Maitre d’” and promised “to remember him with honour.” School friends, singing clubs, and sports clubs did the same. One could almost measure a man’s popularity among his peers by the number of Nachruf printed to commemorate him. When Peter Hartmann died in April 1918, his classmates, sports club, and the Gabelsberger stenography firm placed Nachruf in the Schwanheimer Zeitung. He was remembered variously as “a good friend to all,” “an active member and avid supporter” and, oddly specifically, as “popular among everyone for his stenographic success.”

After reading hundreds of such death notices, one can only conclude that the pinnacle of German chivalry perished in the war. Of course, reality must have been more nuanced; adulterers, disobedient sons, unkind classmates and deadbeat dads surely numbered among the dead as they did the living. Yet whatever their shortcomings, their characters were ultimately fixed in print as “kindhearted” and “loving” — and, in the case of Wolfgang Dietz, “the sunshine of our house.” That was the other side to the men whom propaganda portrayed as killers of babies and rapists of nuns.