How to Knit a Perfect Sock for a Soldier

During World War I, women knitted millions of socks for soldiers at the front. The task of ensuring the quality of these socks fell to organizations such as the Red Cross. To guarantee a “perfect standard of sock for our boys,” they faced more challenges than you might realize.

“The best reason for knitting for the soldiers is that it is hardly possible to make an uncomfortable hand-knitted sock,” wrote a Canadian journalist in 1915. In fact, as anyone who has ever knitted a sock (or attempted to knit one) will know, there are a multitude of ways in which one can make a very uncomfortable handknitted sock indeed. And in the midst of the Great War, with knitters of all ages and skills recruited to “the great army of defense against the unspeakable evil which threatens the world,” these “misfit socks” proliferated.

To be fair, one could hardly expect new or inexperienced knitters to meet the exacting requirements for soldiers’ socks. At the same time, it was imperative that they do so. As the British Red Cross wrote in a letter to Canadian volunteers in 1915, “It is a waste of time and material to make dressings and garments that are useless and we cannot afford to waste either at this time.”

Thus, in order to assist knitters in the production of high-quality, well-fitting socks, the Red Cross and other comforts committees began providing standardized sock patterns together with long lists of do’s and don’ts. A sock had pass three tests to be deemed suitable for a soldier: colour, size, and craftsmanship.

Colour

Patterns from all countries specified grey or natural-coloured wool. In Germany, “feldgrau” or field grey — a kind of greenish-grey — was the official colour of military uniforms and everything was meant to be knitted to match. However, during the autumn of 1914, German producers were unable to meet demand for grey yarn. Allowances were then made for socks in other colours. Grey could not be foregone for gloves, mittens, and wristwarmers, however; Black and other colours were highly visible and resulted in many soldiers being shot in the hand by the enemy. “So only grey wool should be used for such items. On the other hand, it is not absolutely necessary that the stockings also be knitted from grey wool.” Austrian knitters were told to use grey and “any other colour that is as similar as possible to the colour of the field uniform (absolutely not black or red or white or otherwise bright).”

Bright colours were to be avoided not only because they provided an easy target. “Almost any article of clothing may murder you,” Australian newspapers reported in 1915. “The perspiration of the body is apt to dissolve and absorb the colouring dyes, which often contain aniline poisons.” Therefore, another article said, when choosing a yarn for soldiers’ socks, “a wool that has much dyeing matter should be avoided, as it might easily cause blood poisoning if there were even a slight injury to the foot.” Today these assertions may seem oddball at best and conspiratorial at worst. However, documented cases of aniline dye poisoning in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lent credence to the concern at the time. This fear went far beyond Australia, but in the case of Austria-Hungary and Germany, newspapers refuted rather than propagated those claims.

For all the anxiety over dye, “ringed socks” among Australian troops featured a bright stripe; whether on the cuff or the foot of the sock is unclear. Nevertheless, “It is certain that men whose socks have a ring of vivid purple or green can quickly pick them out of a mass in a tent in the early morning, which probably accounts for their popularity.” Stripes were said to be popular among New Zealanders too, though for a different reason. As a writer for the Thames Star remarked in December 1918, “There was a keen demand for striped socks at the front…the theory being that hardly any dead or even wounded men were found to wear them. The real reason for this of course was that very few of this class of footgear was sent out.”

The same belief about the power of striped socks spread among American troops too: “In the trenches there is a pet superstition that the soldier who has a red stripe in his socks will never be hit by bullets.” For this reason, some Red Cross branches encouraged the inclusion of a red stripe. Stripes also served several practical purposes. Firstly, they relieved the monotony of knitting with grey yarn, described by one writer as a “vision of gray, betokening the gray of life, a vision of serene sadness.” They were also an easy way to use up scrap yarn. Finally, Americans, like Australians, used stripes to keep their socks “mated and identified.”

In the early months of the war, some Welsh knitters were told that “heels and toes should be knitted with white wool.” S. Minwel Tibbott documented this style of stocking in rural Wales during the nineteenth century; men’s stockings featured blue-grey as the main colour, while women’s stockings were knitted in black. Why instructions for military socks should specify heels and toes in a contrast colour is unclear. In other countries, contrasting heels and toes rendered a sock unfit for a service. However, as local knitters often supplied local battalions, it may be that the colours of these Welsh socks were meant to remind Welsh soldiers of home.

Size

An acceptable colour having been selected, the sock now had to be knitted to the proper size. Gauge measurements—nowadays calculated as the number of stitches per 4"/10 cm — never appear in these patterns, and this lack of specification caused a plethora of problems. As the Offenbacher Abendblatt lamented, “Everyone knits according to the same pattern, and yet one pair [of socks] hardly resembles another.”

Newspapers frequently printed articles to inform knitters of the correct measurements. In Victoria, Canada, the Daughters of the Empire found it necessary to “call attention to the fact that many socks now being handed in to headquarters are either too short or too long. The following are the correct dimensions…when finished, eleven or eleven and a half inches in length.” While socks of somewhat smaller dimensions were still acceptable, the Toronto branch of the Daughters of the Empire observed that “we do not find the smaller socks as good as those that are more ample.” Australian patterns attempted to provide knitters with some leeway by listing different sizes that could be made ranging from 10½ inches to 11½ inches. These instructions did not eliminate problems, however; Red Cross branches in all combatant countries commonly complained that they received pairs in which each sock differed in length.

According to a German volunteer at a field hospital, socks were usually too small. “We have observed…that the feet of the stockings are knitted much too short, and become uncomfortable. When these stockings are washed, they shrink so much that they become unusable and the soldiers can no longer wear them….We have never seen a stocking knitted too large.” Meanwhile, Austrian newspapers gave precise instructions for measuring socks: “The feet of the socks must be measured as follows: lay them flat on the table and measure from the middle of the heel to the toe. The average size of a man’s foot is 29 centimeters.”

In New Zealand, overly large socks presented problems of their own. “The foot of the average N.Z. soldier is usually medium size, and if the foot of the sock is kept from 10 to 11 inches it will fit the average man. As some very large specimens have lately arrived measuring 12 inches and a little more, it might be well for knitters to keep the inch-tape handy, as eyes are not always to be trusted. One slim young soldier, not long returned, was heard to say that when he put on the socks given to him, the heels went half-way up the leg.”

Although most length-related concerns focused on the feet of the socks, the cuff— from the top of the leg to the beginning of the heel — also received scrutiny. An acceptable cuff ranged from 10½" in some American patterns to 15" in Germany (between 26.5–38 cm). Sometimes pattern writers took pains to point out that this measurement included the ribbing at the very top, which may indicate that some knitters misinterpreted the instructions and made overly long cuffs. In all countries, wool shortages required knitters to use their yarn as economically as possible; “be sparing with the yarn” was even one of the “Ten Commandments of Knitting” published by the German Patriotic Women’s Association.

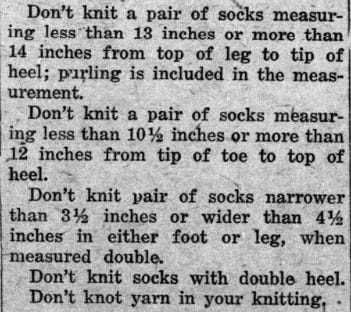

Knitters also had to ensure that their socks were not “narrower than 3½ inches or wider than 4½ inches in either foot or leg, when measured double.” For inexperienced knitters, this was easier said than done. Cläre Preisner, who knitted as a schoolgirl in Germany during the war, later recalled her efforts with some wryness: “My father always said, well, now, isn’t that crazy, those socks, they’re more suited for an elephant than a soldier.”

Craftsmanship

In May 1918, the state of soldiers’ socks plunged The Sun of Sydney, Australia, into deep despair. “Even after all these years of war there are still women who don’t know how to knit socks. That is not to say that they don’t know how to manipulate the needles, but the result is such an appalling spectacle that one wonders who on earth was the guiding spirit that shaped the sock.” The article went on to include a pattern for a “soldier’s sock in thick wool” and three paragraphs about “ERRORS OF KNITTERS” that one should endeavour to avoid at all costs.

Such problems of craftsmanship — the quality of the knitting — were not limited to any one country. American newspapers printed similar articles to their Australian counterparts. Lists like the one of “Important Red Cross Don’ts” from the Sauk Centre Herald in Minneapolis, USA, reveal a wide variety of problems ranging from the cuff to the toe. Reading these litanies of potential monstrosities, it is hard to work up the courage to knit a sock. (As The Sun snarked in another article, “If you would be a knitter of socks be a perfect one, or pass on your wool to someone more experienced.”)

In fact, just two things generated the majority of complaints: the finishing of sock toes and the joining of new yarn. It was here that the twin horrors of knots and seams most frequently occurred. Preventing them became a near obsession.

The goal of completely eliminating knots and seams may at first appear unrealistic and perhaps even unnecessary. In fact, it addressed a very real issue: namely, that knots and seams could kill a soldier. As the Daily Gate City and Constitution Democrat of Keokuk, Iowa, USA, warned its readers, “…a lump or knot brings a blister. If the blister breaks, blood poison sets in and may result in the loss of a foot or life.”

This may sound overly dramatic; we have all experienced blisters — while wearing dyed socks, even — and survived to tell the tale. So why were soldiers so adversely affected? The answer is two-fold. Firstly, they often stood for hours or days with wet feet in the trenches. These conditions encouraged a type of damage to the feet known as “trench foot.” Secondly, in the worst-case scenario, trench foot rendered the skin more susceptible to open sores and blisters, which easily became infected in the unhygienic trenches. These infections could not always be treated. At the time of the war penicillin had not yet been discovered and doctors often had no choice but to amputate infected limbs.

Thus, to save soldiers’ lives, knitters were instructed to splice the end of the old yarn with the beginning of the new yarn. “The two ends to be joined should be shredded, breaking in each one strand about 3in back, another 2in, and so on, according to the number of strands or plies in the wool; then overlap the one strand of the one end over the original wool of the other end, and, holding both ends firmly, twist the wool several times, repeating the twist until the length of the break is knitted.” Knitters could also avail themselves of this simpler alternate method: “The best way to join wool is to put the ends side by side for two or three inches, and knit together for half a dozen stitches.”

As wearers of modern commercial socks will know, the toe is often finished with a thick seam in which the top and bottom of the sock are sewn together. While this seam may not trouble civilians, soldiers were not so lucky. Like knots, seams led to chafing, especially during long marches. In fact, they caused such acute problems that in 1915, Lord Herbert Kitchener popularised a way of weaving together the remaining stitches to close the sock toe without a seam. That method is known today as Kitchener stitch. Some contemporaries called it the “military toe,” a nod to its initial use in military socks. All agreed that “This finishing is far superior to the ordinary method of finishing off, which sometimes leaves a ridge which may be very uncomfortable.”

The Red Cross chapter in Olympia, Washington, USA, admitted that it was, in fact, “possible to make a good toe that is not a Kitchener toe.” Indeed, while the Kitchener toe might have been the preferred method of finishing a sock, patterns from New Zealand to Wales to North Dakota in the United States —nevertheless contained instructions for round toes.

By using a different rate of decreases, the round toe diminishes to a point. The remaining stitches are so few in number that they can be finished off by running the yarn through them and pulling tight to close. It was used in Germany and Austria throughout the war. Even if the Kitchener toe technique had been known in Germany, it may not have been deemed acceptable for use. Patriotism had reached a fevered pitch and all things German were in, while all things foreign were decidedly out. This purge did not stop at mere physical objects (or the heckling and deportation of foreigners). Language, fashion, and culture were to be cleansed of foreign influences: “German customs, German styles, and the German language must become prevalent everywhere…they belong to the rebirth of our people!” In such an environment, a technique named after a British field marshal could hardly be expected to gain popularity.

“Keep plugging”

When socks arrived at Red Cross depots and comforts committee headquarters, volunteers double-checked them for flaws.“Every pair of socks is felt all over for fear there are knots or ends of wool or rough ridges left.” If they discovered a knot, they unpicked it and darned it over.

One American Red Cross branch estimated that 10% of all socks that they received contained faulty toes. These and other “deformed socks” required reknitting — “a waste of time and labor entailed in the uncongenial task of undoing the bad knitting.” There was no way around it, however, and after being deemed suitable, the socks were at last sent on their way.

While it may be a stretch to claim that fresh socks won the war, they certainly played a role in keeping soldiers healthy and in good spirits. As Sergeant-Major Porter of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry told a Red Cross gathering in Toronto: “The minute you stop knitting socks and sewing shirts some Tommy at the front will go needy. Keep plugging. The boys think more of the things you make than they’ll ever tell you.”