Building the Resistance in Legotown

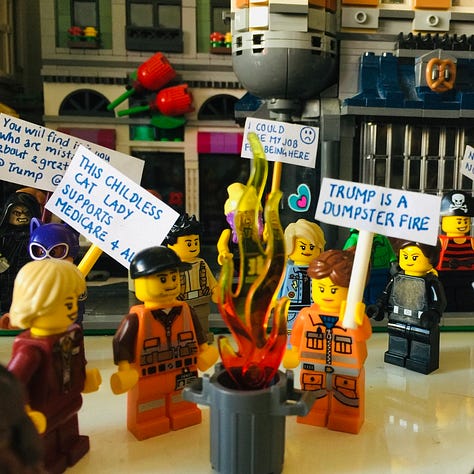

In April 2025, dozens of Lego minifigures in Norway turned out in solidarity with Americans to protest the Trump regime. This is their story.

On 5 April 2025, residents of Legotown, Norway, took to the streets. They carried handmade signs (all suspiciously written in the same handwriting) proclaiming among other things their support of Medicare for all and advising adults to “Just Say NO to Fascism” in much the same way that kids in the 1990s were taught to “Just Say NO to Drugs.”

This gathering was repeated two weeks later on 19 April. Living abroad, I did not have the chance to participate in an in-person protest but I still wanted to Do Something. (Previously, “Doing Something” had entailed designing knitting patterns like the 3D hat, Eat the Rich hat, and Elbows Up cowl. This worked well enough when spring had not yet sprung in the northern hemisphere but as temperatures increased, wearing woolies became uncomfortable and impractical.)

Why Lego?

This project was inspired by “toy protests” in Russia back in 2012. When local governments banned in-person protests, organisers decided to host “nano-demonstrations” featuring toys with signs that declared their displeasure. Andrey Teslenko, who coordinated efforts in Barnaul, Siberia, said that although the demonstration in his city only involved toys, it was still taken very seriously: “The police filmed us and wrote down all slogans we had written on the toys’ signs.” Later, officials banned the toy protests too. But the damage was already done: the absurdity of the authorities’ stance and the police response turned them into objects of ridicule rather than fear, if only for a while.

For this specific project, it made sense to use Lego because we have several hundred litres of the stuff and because of its iconic status around the world. The Lego minifig can be customised in infinite ways yet is also instantly recognisable. Furthermore, the history of the minifig as well as Lego’s Scandinavian origins provided an avenue for me to explore contemporary questions about immigration, integration, and race.

Yes, it sounds pretentious when I put it like that. Sorry. But there’s a reason why this project features only yellow minifigs. This was a deliberate choice rooted in Lego’s original philosophy from when they created the yellow minifig—they wanted to emphasize the figures’ universality by using a skin tone that isn’t found in real life. Furthering this social democratic ethos is also a component of the protest, both against the Trumpian oligarchy that seeks to divide rather than unite as well as against the current political climate in Norway, where the rightwing nationalist party is polling at record levels.

By choosing an iconic Scandinavian toy to make its point, this project also asks viewers—especially ones that like to shit on foreigners and scream about preserving Scandinavian culture—to consider what happens when immigrants master and then subvert Scandinavian ways of being and doing. Are we using Lego “wrong” when we place minifigs in the traditional colour among traditional architecture with an intention that is very untraditional? Or are we taking it to the next level? I’ve asked a similar question with my pattern collection Knitting from Søndre Nordstrand, which I designed in response to anti-immigrant sentiment in the wake of a murder in my neighbourhood. The patterns use traditional Norwegian textile motifs but are combined in non-traditional ways. For some people, these kinds of modifications are a travesty. For others, it shows the extent of my integration.

The Possibilities of Protesting

I quickly realised that a Lego protest opened up opportunities for absurdist commentary, and took full advantage of them.

At the same time, the initial protest still felt quite isolated. Only when I shared pics on Ravelry, a knitting forum, did I realise the possibilities for community-building. In a thread about the protests from 5 April, many people mentioned that poor health, job commitments, or unforeseen circumstances had prevented them from attending. In the same thread, the positive response to the Lego protest overwhelmed me. As such, it seemed completely natural to invite Ravelry members to join me in Legotown for the next demonstration.

Messages trickled in for about 10 days, comprising in the end about 40 participants: “Curly brown hair, glasses, dog” — “any science minifig with a brown ponytail” — “female, nearly waist length silver hair, glasses, old.” I endeavoured to recreate each person as accurately as possible (although many more people wore glasses than I had anticipated and towards the end people had to make do with sunglasses. There were also many fewer blond people than I had expected). One person asked to be represented as a shark while others requested science fiction or fantasy outfits. Some of them came with their pets, others with their kids, still others with their knitting. Wands from the Harry Potter Lego sets stood in for knitting needles.

The mood on the street reminded me of what Norwegians call a “folkefest” or people’s party. Throughout the day, I reconfigured the constellations of minifigures so that people could move around, meet each other, and take photographs together. People from Ravelry mingled with Star Wars storm troopers, skeletons, and ghosts, as well as construction workers, baristas, and bakers.

Three protesters specifically asked to stand apart from the main group in order to show solidarity with people who are protesting alone in real life—you can see them at different points on the roofs in the photo above. It may be strange to think that one can show solidarity in solitude, but I later saw a post on Reddit that underscored to me how important the image of a single protester could be. The post had been written by a man in Maine who was protesting alone in his community. He had received death threats but refused to back down. As one of the Legotown protesters told me about going it alone:

I think it supports others who do not have the option to join a crowd and yet get out there. When they see that others do so, others may gain courage to do so [too].

Further Reflections

Protesting in Legotown is safe. You can’t get renditioned, arrested, beaten by police, or attacked by counter-protesters. Is it therefore a lesser form of protest because we do not put our real bodies in potential danger and are less likely to suffer the consequences of our actions? Or does this anonymity free us from constraints that would temper our approach in real life? And do the answers to these questions even matter?

Srdja Popovic, in his book Blueprint for Revolution, writes about the necessity of creating a broad movement for change that includes as many people as possible. To do so, multiple ways to protest are usually needed. Popovic, who was one of the leaders of the Otpor! resistance group against Slobodan Milosevic in the late 1990s, remarks that street protests in Serbia were almost exclusively for young adults as police often used violence against demonstrators. Yet the elderly and the underage wanted to do their part too. The solution: coordinated noise-making. Every night at the same time, people opened their windows and banged their pots and pans to show their displeasure with Milosevic. It was solidarity in audible form, and accessible to anyone regardless of their age or physical fitness.

I will leave the last word to some people who really know what they’re talking about.

(More pics on my Instagram.)